Moral and Sentimental Reflections

යමෙක් අඩි 300ක් උස්වූ අභයගිරි* චෛත්යයේ ඉහළ උස්බිමට නැගගතහොත් ඔහුට කුරුල්ලෙකුගේ ඇසකින් මෙන් මේ කලාපයේ කදිම ගුවන් දර්ශනයක් දැක බලාගන්න පුළුවන්. බටහිර සහ උතුරු දිශාවේ, සාමන්ය ඇසකින් දැකිය හැකි සීමාව දක්වාම විහිදුණු, කඳු හෙල් වලින් බාධා නොවූ, මට්ටම් වූ තැනිතලා බිමක් ඔහු ඉදිරිපිට එහිදී දෘශ්යමාන වෙනවා.

|

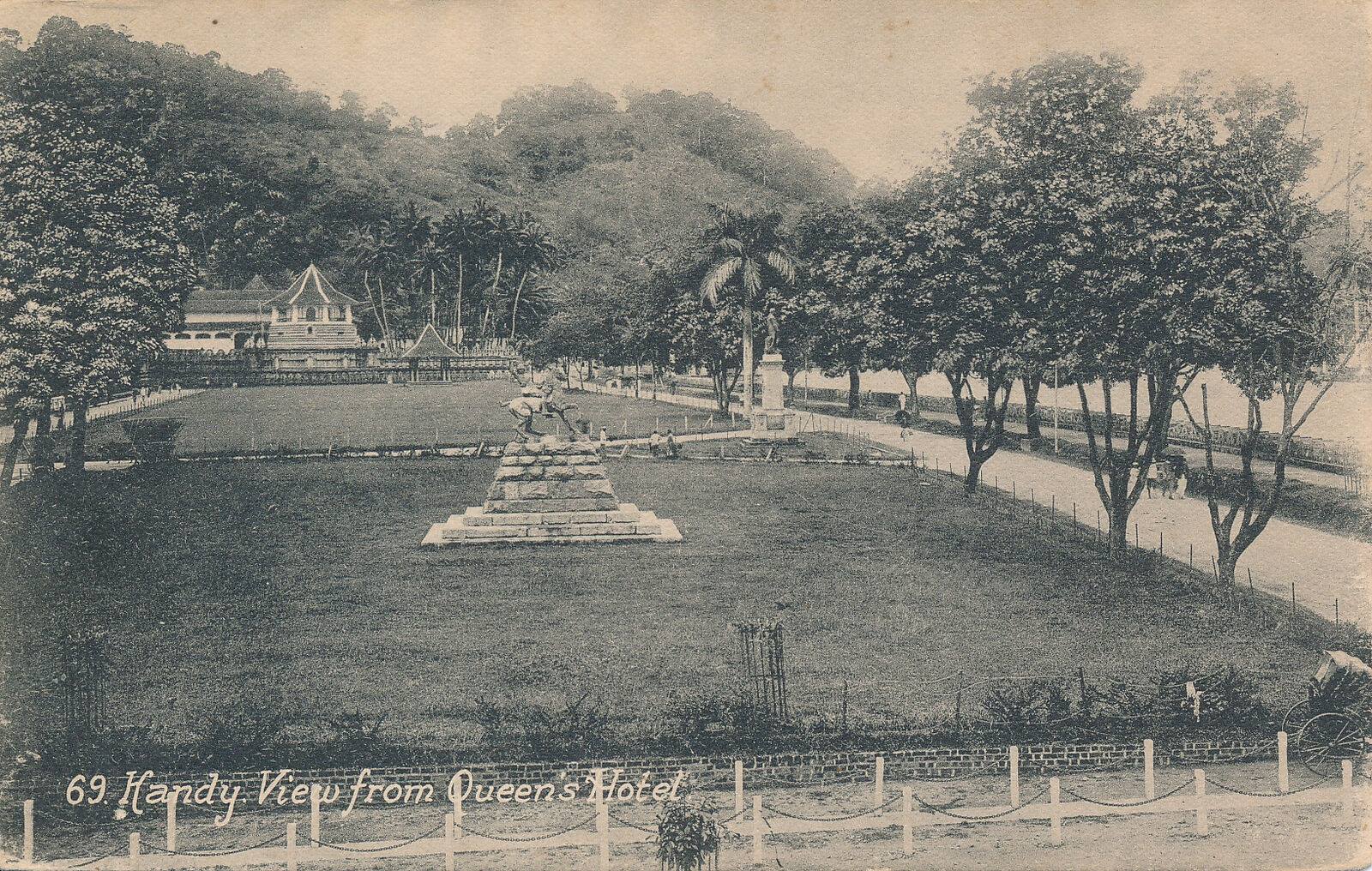

| Mahamevuna Uyana in 1896 by Henry W. Cave |

අභයගිරි චෛත්යයේ සිට අද දකින දර්ශනය

ජලාශ කිහිපයක් සහ, ආගන්තුක එනමුත් මේ කලාපයේ දුලබ ලෙස හෝ පවත්නා පොල් රුප්පා හැරෙන්නට මේ තැනිතලාව වැහිලා තියෙන්නේ මහා ඝන වනාන්තරයෙන්. හැම පැත්තකටම මේ ඝන වනන්තරය පැතිරිලා. සෑම තැනකම අළුවන් කොළ පැහැයෙන් එකම විදිහට වර්ණ ගැන්වූ කලාලයක් පොළව මත අතුරලා වගේ. වර්තමානයේ අනුරාධපුරයේ ඇති ගම්මානයවත් මේ තත්වයට වැඩි වෙනසක් එක් කරලා නැහැ. එයත් තුරු ගොමු ගැවසීගත් ඉතා කුඩා ගම්මානයක්.

|

| The Abhayagiri (Jetawanarama in present) Dágoba, Anuradhapura. View from the west. (ca. 1870) photographed by Joseph Lawton (© Victoria and Albert Museum) |

මේ වනන්තරය හරහා ඉතා පටු වන පෙත් දිවෙනවා. මේ වන පෙත් අතර සැතපුමෙන් සැතපුමට තැනින් තැන, මා පෙරදී සඳහන් කල ආකාරයේ නටඹුන් විසිරී ගොස් තියනවා. ඒ පෞරාණික අනුරපුර නගරයේ අද ඉතිරිව දක්නට තියෙන්නේ මේ දේවල් විතරයි.

|

| Old Map of Anuradhapura according to 1890s identifications [Image Courtesy: www.lankapura.com ] |

යහපත් හා භාවාත්මක අන්තරාවලෝකනය

මේ වගේ මාතෘකා සම්බන්ධව යහපත් ලෙසින් නැවත නැවත කල්පනා කර බලන්නට ඇතිවන පෙළඹවීම මම හිතන්නේ බොහොම ප්රබලයි. මා ගැන කතා කළොත් මට කියන්න තියන එකම දේ, මම මේ දේවල්, මේ දර්ශනයන් අතරින් ගමන් කළේ අවංකවම මගේ කෘතඥතාව පුද කරන හැඟීමකින්. මොකද මේ දේවල් අයිතිවෙන්නේ කවදාවත් යළි නො එන මියගිය අතීතයකට.

අනියත බව විද්යාමාන කරනා මේ සියලුම ආයාසයන් කාලය විසින් අතුගා දමලා. යථාකාලයේදි එය කාලයේ කුණු බක්කියකට වැටේවි (අපේ දේවල් වලට වුණත් ඒක එහෙමයි). ඒ කාරණය සම්බන්ධයෙන් නම් කවදාවත් අපට කෘතඥ පූර්වකව කතා කරන්න බැරි වේවි.

|

| An ancient stone canopy situated near Abayagiri Monastery (Dhammaruchi Sect) Anuradhapura (ca. 1910) [Image Courtesy: www.lankapura.com ] |

සිතන්න... මේ මිනිස්සුන්ගේ අභිමානය හෝ මෝඩකම් හෝ විදහා දැක්වෙන මේ සියලුම සිහිවටනයන් නිර්මාණය කර තිබුණේ නොනැසී පවතියි යන අපේක්ෂාවෙන් නම්; වර්තමාන අපගේ විශිෂ්ට ප්රයෝජනවත් නිර්මාණයන් පවා ඇත්තේ එලෙස පවතින්නට නම්; පොළව මත මෙලෙසින් පැටවෙන බර කොච්චරක් වෙයිද? මොන තරම් පීඩාවක් ඉන් ඇති වෙයිද!

මහරජවරු මෙවන් යශෝධර මාළිගා, මන්දිර, ප්රතිමා සහ විහාර තැනවීමට හේතු කාරණාව වුයේ, පූර්වයේ වූවන් ජනආකර්ශනයෙන් පරදවීමේ සහ අනාගත මෙවන් මානව උත්සහයන් ව්යර්ථ කරවාලීමේ චේතනාවයි. එයින් ඔවුනගේ අභිප්රාය වූයේ තම නාමය ලෝක අවසානය දක්වාම චිරස්ථායීව පතළ කරගැනීමයි. එනමුත් කාලය ඉතා ප්රඥාවන්තව මේ සියලුම දේවල්, ඒවායේ කතුවරුන් එහි ගමන් මගින් ඉවත්ව ගිය කල්හී ඉතා ඉක්මනින් අස් පස් කර දැම්මේ, ඒවායේ යටි අරුත් ප්රකාශ කල හැකි පමණට යමක් පමණක් ඉතිරි කරමින්.

|

| Stone figure of King Dutugemunu, Ruvanvelisaya Dagoba in Anuradhapura (ca. 1903) [Image Courtesy: www.lankapura.com ] |

තරමක හොඳ නගරයක්ම ඉදි කල හැකි ගඩොල් කැට විශාල ප්රමාණයක් දරාගත් අති විශාල දාගැබ්, ගොඩ නැගී තියෙන්නේ මහා ශාස්තෘවරයාණන් වහන්සේ නමකගේ හිසෙහි එක කෙස් රොදක් නිදන් කර තබන්න. මේ මුළු කාලපරිච්ඡේදය පුරාම ඉදිවුණ මහානුභාවසම්පන්න විහාරයන් සහ ප්රතිමා සහ සිතුවම් සහ මාළිගා සෑම දෙයකම ඉතා කුඩා සදාතන සුන්දර පරමාණුක අණුවක් නිධන් ගත වෙලා. එයට නිදහස් වෙන්නට ඉඩදී එයට නියම වූ ගමන් මඟේ යන්නට ඉඩ හරිමු.

අපේ ශරීරය මිය යන එක කොච්චර හොඳ දෙයක්ද! කාලයත් සමඟ විනාශ වී යන එයට අපි මොනතරම් ස්තූතිවන්ත වෙන්න ඕනද? හිතන්න අපගේ මේ සංසාර චාරිකාවේ අපට දඬුවමක් නියම වුනොතින් සියලුම දෙනා එකම රූප කායකින් දිස්වෙන්න, එකම කවටකම කරමින් නැවත නැවත දිවි ගෙවන්න, කලින් කල නුවණැති වදන් නැවත නැවත පුනුරුච්චාරණය කරන්න, පෙර පැවති අභිමානයම නැවත නැවත දල්වාගන්න, පෙර ලැබූ නින්දා අපහාසම නැවත නැවත ඉවසන්න, සියවස් ගණනාවක් පුරාම ක්රමක්ක්රමයෙන් වැරහැලි වන පෙර ඇඳි පුස් බැඳුණු ඒ වස්ත්රයම නැවත නැවත අඳින්න; එය මොන වගේ ඉරණමක් වෙයිද! නැහැ. අපි දැනගන්න ඕනි මේ සංසාර චාරිකාවේ ඊට වඩා දෙයක්, වඩා හොඳ දෙයක් ඇති වග.

මහජන වියදමින් සකස් කොට ගල් ඔරු තුළ දමා ඇති බත් ආහාරයට ගන්නා අකර්මණ්ය වූ මේ භික්ෂූණ්; ඔවුන් අතින් නිමක් නැති ප්රලාපයන් ලෙස ලියවෙන මේ කෘති; අලංකාර රාජකීය ඇඳුම් පැළඳුම් හැඳි ඉතා බලවත් රජවරුන්; ඔවුන්ගේ අන්තඃපුරය; වියරු වැටී කරනා ඔවුන්ගේ යුධ අරගල; මේ සත්ව රෝහල්; වනලැහැබ මැද්දෑවේ මංමුළා වූ මේ මහා නගරයන්හී නටඹුන්; මේ දැවී අළු වී ගිය, ඇලෙක්සැන්ඩ්රියානු පුස්තකාලයන් වන් පුස්තකාලයන්; මේ කැඩී බිඳී පොළවේ වැළලී ගිය ග්රීක ප්රතිමා වැනි ප්රතිමා; මේවා අතරින් කල් පවතින්නට හැකි සියල්ලක්ම තවම නොනැසී පවතිනවා. ඒවා කාලයට ඔරොත්තු දේවි. නමුත් අන් සියල්ලක්ම අනිවාර්යයෙන්ම ගමන් මගින් ඉවත් වී යාවි.

“තැපල් කරත්තයේ” රාත්රියක්

|

| Native Bulls photographed by Scowen & Co. [Image Courtesy: www.imagesofceylon.com ] |

ඇත්තටම කවුරුහරි පෙර සඳහන් කල තැපැල් කරත්තයේ යක්කු ගස් නගින රාත්රී කාලයේදි හැල්මේ ආපසු අනුරාධපුරේ ඉඳන් දඹුල්ලට සැතපුම් 42ක් දුරකතර ගෙවාගෙන එනවා නම් (ළඟම ඇති අශ්ව කරත්තය මුණගැහෙන්න) මඟීන් පස් හය දෙනෙක් අතර මිරිකී ඉන්නට ඔහුට සිදු වෙනවා. කරත්තය තුළ දමා ඇති එකට තද වූ ගමන් පොදි ලට පට බඩු මුට්ටු අතරේ කෙනෙකුට කකුල තියාගන්න තැනක් හොයාගන්න ඉතා නිෂ්ඵල උත්සහයක් දරන්නට වෙනවා. එහෙම නැතිනම් කරත්ත රාමුව හිසේ සහ පිටේ වැදෙන එක වළක්වගන්නට උත්සහ කරන්නට වෙනවා. පුංචි ක්රියාශීලි බ්රහ්මිණ ගවයන් අඳුරේ උනන්දු කරවන්න තොරක් නැතිව නද දෙන සීනුවේ කිංකිණි නාදය, කරත්ත රියදුරාගේ කෑ ගැසීම් සහ ඔහුගේ කෙවිට පහරවල් රෑ තිස්සේ පුරාම කෙනෙකුව හොඳ අවදියෙන් තබන්න පුළුවන්. ඒ නැතත් ගොන් කණ්ඩායම මාරු කරන්නට නවත්තන පාර අද්දර පැල් කොටන් අසල ලාම්පු අත දරාගත් අඳුරු රූප කායන් අතර සිද්ධ වෙන දිගු සංවාදත්, පාරෙ තත්වයත්, සහ නිතර ගැවසෙන වල් අලියෙක් මුණ ගැහෙන්න තියන සම්භාවිතාවත් ඊට බලපානවා. මේ සම්පූර්ණ පැය දොළහක දිගු කාලය තුළදී කෙනෙකුට සෑහෙන ඉඩ කඩක් ලැබෙනවා අපගේ මේ පුංචි මානුෂීය වෑයමේ අස්ථායි ස්වභාවය හෝ නිෂ්ඵල ස්වභාවය පිළිබඳ ඊට ඔබින යම් කිසි ආවර්ජනයක යෙදෙන්න.

|

| Places Edward Carpenter had travelled before Anuradhapura. Map of the Ceylon Government Railways (A guide to Kandy by Skeen, George J.A, 1903) |

“ආදම්ගේ ශිඛරය මතින් එලිෆන්ටා ගුහා වෙත – ලක්දිව සහ ඉන්දියාවේ රූප සටහන්” : එඩ්වඩ් කාපෙන්ටර්

සයවන පරිච්ඡේදය : අනුරාධපුරය, වන අරණේ නටබුන් නගරය.

From Adam’s Peak To Elephanta : Sketches in Ceylon and India by Edward Carpenter

CHAPTER VI: ANURADHAPURA – A RUINED CITY OF THE JUNGLE.

If one ascends the Abhayagiria dagoba, from its vantage height of 300 feet he has a good bird's-eye view of the region. Before him to the west and north stretches as far as the eye can see a level plain almost unbroken by hills. This plain is covered, except for a few reservoirs and an occasional but rare oasis of coco-nut palm, by dense woods. On all sides they stretch, like a uniform grey-green carpet over the earth ; even the present village of Anuradhapura hardly makes a break,—so small is it, and interspersed with trees. Through these woods run narrow jungle paths, and among them, scattered at intervals for miles and miles, are ruins similar to those I have described. And this is all that is left to-day of the ancient city.

I suppose the temptation to make moral reflections on such subjects is very strong I For myself I can only say that I have walked through these and other such scenes with a sense of unfeigned gratitude that they belong to a past which is dead and done with. That Time sweeps all these efforts of mortality (and our own as well) in due course into his dustbin is a matter for which we can never be sufficiently thankful. Think, if all the monuments of human pride and folly which have been created were to endure indefinitely,—if even our own best and most useful works were to remain, cumbering up the earth with their very multitude, what a nuisance it would be I The great kings caused glorious palaces and statues and temples to be made, thinking to outvie all former and paralyse all future efforts of mankind, perpetuating their names to the end of the years. But Time, wiser, quickly removed all these things as soon as their authors were decently out of the way, leaving us just as much of them as is sufficient to convey the ideas which underlay them, and no more. As a vast dagoba, containing bricks enough to build a good-sized town of, is erected to enshrine a single hair from the head of a great man, so the glorious temples and statues and pictures and palaces of a whole epoch, all put together, do but enshrine a tiny atom of the eternal beauty. Let them deliver that, and go their way.

What a good thing even that our bodies die ! How thankful we ought to be that they are duly interred and done with in course of time. Fancy if we were condemned always to go on in the same identical forms, each of us, repeating the same ancient jokes, making the same wise remarks, priding ourselves on the same superiorities over our fellows, enduring the same insults from them, wearing the same fusty garments, ever getting raggeder and raggeder through the centuries—what a fate ! No ; let us know there is something, better than that. These swarms of idle priests who ate rice out of troughs at the public expense ; these endless mumbo-jumbo books that they wrote ; these mighty kings with their royal finery, their harlots, and their insane battles ; these animal hospitals ; these ruins of great cities lost in thickets ; these Alexandrian libraries burnt to ashes ; these Greek statues broken and burled in the earth—all that is really durable in them has endured and will endure, the rest is surely well out of the way.

Certainly, as one jogs through the mortal hours of the night in that said mail-cart, returning the fortytwo miles from Anuradhapura to Dambulla (where one meets with the nearest horse coach), wedged in with five or six other passengers, and trying in vain to find a place for one's feet amid the compacted mass of baggage that occupies the bottom of the cart, or to avoid the side-rails and rods that impinge upon one's back and head—kept well awake by the continual jingling of bells and the yells and thwacks of the driver, as he urges his active little brahminy bulls through the darkness, or stopping to change team at wayside cabins where long conversations ensue, between dusky figures bearing lamps, on the state of the road and the probabilities of an encounter with the rogue-elephant who is supposed to haunt it—all those twelve long hours one has ample time to make suitable reflections of some kind or other on the transitory and ineffectual nature of our little human endeavor.

ලක්දිව ගමන් සටහන් පිටු අංක: 46

Comments

Post a Comment