Cinghalese Rice Fields and Mode of Life

අඩි 50ක් විතර උස පොල් ගහේ කඳ දිගේ කෙළින්ම ඉහළට නැග්ග පුංචා බොහොම අවදානම් සහිත ගමනක් ගියේ. කඹයකින් හදාගත්ත තොණ්ඩුවක්, යටි පතුල් දෙකෙන් පොල් කඳ තදින් බදලා අල්ලගන්න පුළුවන් වෙන විදිහට කකුල් දෙක වටා දාගෙන, අත් දෙකෙන් පොල් කඳ බදාගෙන, දණහිස් දෙක කන්දෙක වෙනකන් උස් කර කර නගින්නෙ හරියට ගෙම්බෙක් පීනනවා වගේ.

|

| Singhalese Boy boy Climbing a Coconut Tree [Image Courtesy: www.imagesofceylon.com ] |

සිංහල ගැමියන්ගේ බැත, කෙත සහ ජීවන මංපෙත්

සිංහලයන්ගේ සියල්ලම පොල්ගස තමයි. පොල් ගෙඩියේ මදේ ගන්නවා ආහාරයට. එක්කෝ බතුත් එක්ක කන්න පුළුවන් ව්යංජනයක් විදිහට හදාගන්නවා, නැතිනම් බතුයි සීනියි දාල හදන පැණිරස කෑමක (අග්ගලා) රසය වැඩි කරන්න දානවා. පොල් කටුව පාවිච්චි කරනවා වතුර බොන කෝප්පයක් විදිහට. නැතිනම් ගන්නවා ප්රාථමික තලයේ හැන්දක් විදිහට. ගොරෝසු කෙන්ද පාවිච්චි කරනවා ලණු, කඹ සහ පාපිසි හදන්න.

|

| Peasants Making Coconut Oil Using Sekkuwa. (ca. 1910) photographed by Skeen & Co. [Image Courtesy: Threeblindmen Photography Archive - Ceylon - Archival Pictures] |

කිරි කිරි ගාන කර්කශ සද්දයක් ඇති පුරාතන මෝලක (සෙක්කුව) ගොන්නු පාවිච්චි කරලා පොල් ගෙඩියෙන් හිඳගන්න තෙල්, සෑහෙන වාණිජ වටිනාකමක් තියන භාණ්ඩයක්. ඒවා පාවිච්චි කරනවා කොණ්ඩයට සහ ශරීරයට හොඳ සාත්තුවක් ලබා දෙන්න. ඒ වගේම ඔවුන්ගේ කුඩා පිත්තල පහන් දල්වන්නත් වෙනත් කටයුතු සඳහාත් මේ පොල් තෙල් ප්රයෝජනයට ගන්නවා. පොල් ලී කඳ ඔවුන්ගේ ගෙපැල් වල සැකිල්ල හදාගන්න භාවිත කරනවා. පොල් අතු, වහලයට හොඳ සෙවිල්ලක්. පොල් අත්ත වියාගත්තම ස්වභාවිකම පැලැල්ලක් සකස් කරගන්න පුළුවන්. ඒ වගේ දේශගුණයක ගෙපැලෙ බිත්ති වලට සෑහෙන වැදගත් කමක් මේ පැලලි එක් කරනවා. ඇජැක්ස් එහෙ එංගලන්තේ පොල්ගස් නැතැයි කිරාට කිව්වහම ඔහු දැක්වූවේ බොහොම අව්යාජ විමතියක්.

"තමුන්නැහෙලා එතකොට ජීවත් වෙන්නෙ කොහොමැයි?"

|

| Rice Fields, Badulla, (ca.1870) photographed by Scowen & Co. |

සිංහලයන්ගේ අනික් ප්රධාන වැවිල්ල වෙන්නේ හාල්. කළුවගේ පවුලෙ අයට අයත් වෙච්ච කුඹුරු ඔක්කොම තියෙන්නේ අපට පහළින් දෙණිය පල්ල දිගේ විශාල කට්ටි විදිහට. ඒවා හෙල්මළු ක්රමේට පටු තීරු තට්ටු ආකාරයෙන් දෙණියෙ ඉඳන් කන්ද උඩටම විහිදී ගොස් තිබුණා. ජල සම්පාදනය කාරණය හේතු කරගෙන කුඹුරු සෑම විටකම තියෙන්නේ එක මට්ටමක පිහිටි කට්ටි විදිහට. මේ හැම එකක් වටේම අඩියක් දෙකක් උස, පහත් පස් වැටියක් තියනවා. ළඟ පාතක වතුර හොයාගන්න තියනවා නම් මේවා කඳු බෑවුම උඩටම තට්ටු විදිහට දකින්න පුළුවන්. හරියට ඉතාලියෙ මිදි වතු වගේ.

|

| Farmers Ploughing a Paddy Field photographed by Scowen & Co. [Image Courtesy: www.imagesofceylon.com ] |

වැහි කාලෙදි සහ වැහි කාලෙ ඉවර වුණාම, බිම් මට්ටමෙන් මට්ටමට පිළිවෙලින් ජලය ගලා බසිනවා. හරියටම කියනවනම් දෙගොඩ තලා යනවා. මේ අස්සේ සී සෑමත් පටන් ගන්නවා. මේ සඳහා ග්රාම්ය, මෙල්ල කරන්න අමාරු නගුලක් භාවිත කරනවා. මොල්ලිය සහිත හරක් බානක් හෝ මී හරක් බානක් යොදාගෙන තමයි මේ නගුල අදින්නේ.

|

| Water buffalo is used to plough the paddy fields [Image Courtesy: www.lankapura.com ] |

වපුරන්න පටන්ගන්නේ වතුර බැහැගෙන යනකොට. ගොයම් ගස් ඉක්මනටම දළු දානවා. දීප්තිමත් කොළ පැහැයක්. බාර්ලි වගේ උසයි. වී කරල් නම් "ඕට්ස්" වලට සමානයි. සති හතකින් අටකින් විතර අස්වැන්න නෙලාගන්න පුළුවන්. එළවළු ව්යංජනයක් එක්ක හරි පොල් සම්බෝලයක් එක්ක හරි ගන්න තම්බාගත් බත, ලංකාවේ ඉන්න සියලුම ස්වදේශිකයන්ගේ ප්රධාන ආහාරය. දවසට ආහාර වේල් දෙකයි. දරිද්රතාවයෙන් පෙළෙන කෘෂිකාර්මික ප්රදේශ වල නම් ආහාර වේල් එකයි. ඒ පළාත් යන්තම් පිරිමහගෙන කල දවස ගෙවන හැටි ඔවුන්ගේ කෘශ ශරීර සාක්ෂි දරනවා. ඔවුන් පාන් පාවිච්චි කරන්නෙ නෑ. ඒත් හාල් පිටි, ගිතෙල් සහ කිතුල් හකුරු පාවිච්චි කරලා පැණි රස කෑමක් හදා ගන්නවා.

|

| A Rice Bin or Bissa photographed by Skeen & Co. [Image Courtesy: Threeblindmen Photography Archive - Ceylon - Archival Pictures] |

මේ සහෝදරයන්ගේ ගෙපැල බොහොම ආදි තාලේ ගෙයක්. අඩි දොළහ අටේ වගේ වපසරීයක් තියන, කාමර දෙකකට බෙදපු, අතු සෙවිලි කල කුඩා තැනක්. වේවැලින් හදපු විශාල බිස්සක වී ගබඩා කරල තිබුණා. පෙට්ටගමක් දෙකක්, උයන පිහන මැටි වළං, ගිනි දැල්වූ බිමක්, තිබ්බට පුටුවක්වත් මේසයක්වත් තිබ්බේ නෑ. බිත්තියේ එල්වූ ඡායාරූපයක් දෙකක් හැරෙන්නට සභ්යත්වයට ළඟා වූ ලකුණක් විදිහට යන්තම් හරි දකින්න තිබුණේ නිදාගන්න තිබිච්ච වේවැල් වලින් හදපු කවිච්චිය විතරයි. මේ කවිච්චිය මොක වුණත් බොහොම සුඛෝපභෝගී දෙයක් විදිහට ගණං ගන්න පුළුවන්, මොකද සිංහලයෝ හැමවිටම නිදා ගන්නේ බිම හන්දා. අපි එහෙ ටික වෙලාවක් කතා බහ කර කර හිටියා. මේ අතරේ කලින් කලට විශාල පොත්තක් ඇති පොල් ගෙඩි විශාල ශබ්දයක් නගමින් ගස් වලින් බිමට වැටුණා. (මේ ගැන නම් බොහොම ප්රවේසම් වෙන්න ඕනා.)

“ආදම්ගේ ශිඛරය මතින් එලිෆන්ටා ගුහා වෙත – ලක්දිව සහ ඉන්දියාවේ රූප සටහන්” : එඩ්වඩ් කාපෙන්ටර්

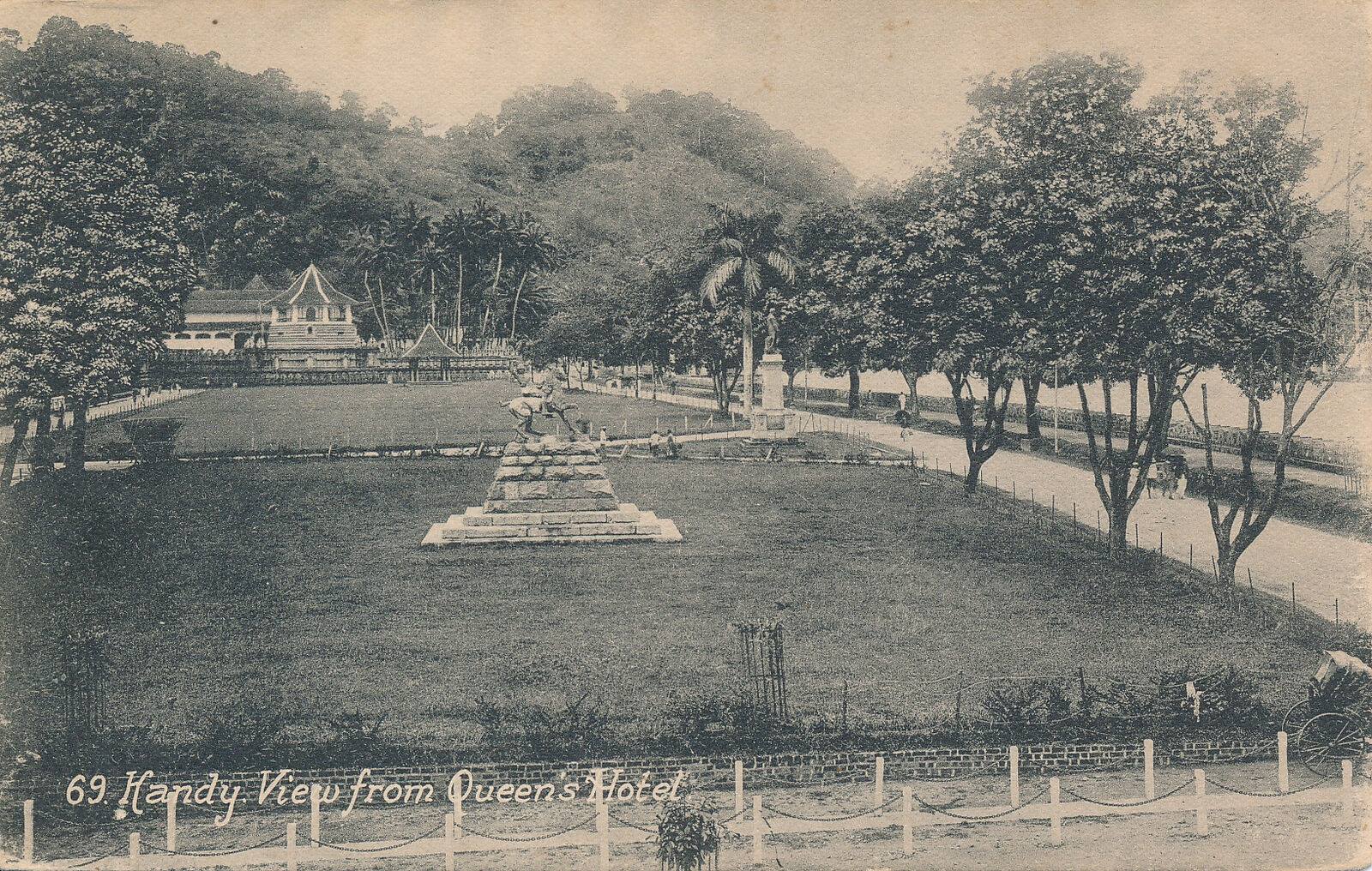

දෙවන පරිච්ඡේදය : මහනුවර හා පිටිසර ජීවිතය

From Adam’s Peak To Elephanta : Sketches in Ceylon and India by Edward Carpenter

CHAPTER II: KANDY AND PEASANT LIFE

To see Punjha go straight up the stem of a coco-nut tree fifty feet high is a caution ! He just puts a noose of rope round his two feet to enable him to grasp the stem better with his soles, clasps his hands round the trunk , brings his knees up to his ears, and shoots up like a frog swimming!

The coco-nut palm is everything to the Cinghalese : they use the kernel of the nut for food, either as a curry along with their rice, or as a flavoring to cakes made of rice and sugar ; the shell serves for drinking cups and primeval spoons ; the husky fibre of course makes string, rope, and matting ; the oil pressed from the nut, in creaking antique mills worked by oxen, is quite an article of commerce, and is used for anointing their hair and bodies, as well as for their little brass lamps and other purposes ; the woody stems come in for the framework of cabins, and the great leaves either form an excellent thatch, or when plaited make natural screens, which in that climate often serve for the cabin walls in place of anything more substantial. When Ajax told Kirrah that there were no coco-palms in England, the latter's surprise was unfeigned as he exclaimed, " How do you live, then ? "

The other great staple of Cinghalese life Is rice. Kalua's family rice-fields lay below us in larger patches along the bottom of the glen, and terraced in narrow strips a litde way up the hill at the head of it. The rice-lands are, for irrigation's sake, always laid out in level patches, each surrounded by a low mud bank, one or two feet high ; sometimes, where there is water at hand, they are terraced quite a good way up the hillsides, something like the vineyards in Italy. During and after the rains the water is led onto the various levels successively, which are thus well flooded. While in flood they are ploughed—with a rude plough drawn by humped cattle, or by buffalos—and sown as the water subsides. The crop soon springs up, a brilliant green, about as high as barley, but with an ear more resembling oats, and in seven or eight weeks is ready to be harvested. Boiled rice, with some curried vegetable or coco-nut, just to give it a flavor, is the staple food all over Ceylon among the natives — two meals a day, sometimes in poorer agricultural districts only one ; a scanty fare, as their thin limbs too often testify. They use no bread, but a few cakes made of rice-flour and ghee and the sugar of the chageri palm.

The brothers' cabin is primitive enough—just a little thatched place, perhaps twelve feet by eight, divided into two—a large wicker jar or basket containing store of rice, one or two boxes, a few earthenware pots for cooking in, fire lighted on the ground, no chair or table, and little sign of civilisation except a photograph or two stuck on the wall and a low cane-seated couch for sleeping on. The latter however is quite a luxury, as the Cinghalese men as often as not sleep on the earth floor.

We stayed a little while chatting, while every now and then the great husked coco-nuts (of which you have to be careful) fell with a heavy thud from the trees.

ලක්දිව ගමන් සටහන් පිටු අංක: 12

Comments

Post a Comment